A common problem:

This Bayou acoustic dreadnaught guitar came to me with a problem that is more common than need be: The bridge lifted off because of string tension, and well lets face it because of traditional construction methods that just do not belong in modern guitar design.

First of all, Bayou guitars have an alligator as part of the logo even though they were made in Vancouver Canada by the owner of the Westcoast Music store where the only alligators are in the zoo. Very little information can be found on these instruments, but from what I can tell they were made between 2005 and 2010, I may be wrong, but the first mention of them I could find was from 2006, but now (2015) the website is gone, and the facebook page has had no new entries since 2010. The stores website is still up and running, but they do not mention the Bayou brand anywhere.

From what I did read, they were sold for a very low price, but are described to be of better quality and sound you could only find in brand name instruments selling for twice the money. I too was surprised by the great tone and materials used on this guitar when the owner told me how much it cost when he bought it brand new in 2006, although I did find one flaw in it's construction: The use of hide glue, which although strong enough initially, can and does deteriorate over time, and is very susceptible to higher temperatures and humidity. It's owner relocated from Vancouver to somewhere in Arizona where it can get extremely hot, and now lives here in South Bend Indiana, where humidity is prevalent, and somewhere in there the bridge came partially undone, raising the action considerably.

The repair:

When the owner contacted me, he wrote that the action had gone south, and the first thing that came to mind was a warped top. When he showed up with the guitar I pointed out that the bridge was coming undone, and sooner or later may pop off with a loud noise and even possible injury, let alone the action being the least of his worries. The top was only slightly warped which happens to most good sounding guitars, and the saddle was shorter than the recess it was in, and had slipped so that the strings did not align well with the fingerboard, see what I mean?.

Knowing that the bridge would have stayed put had a modern glue been used, I was sure that hide glue was the culprit, and used it's enemy; heat to remove the bridge completely, so that I could proceed with repairs. I also noticed that the bridge was not what I would consider done before it was glued down in the first place, as there were obvious saw and course sanding marks showing.

Once I had removed the bridge I also noticed that the gluing surface was smaller than the bridge itself, and the overlapping finish of the guitar's top which is raised may have also contributed to the malfunction.

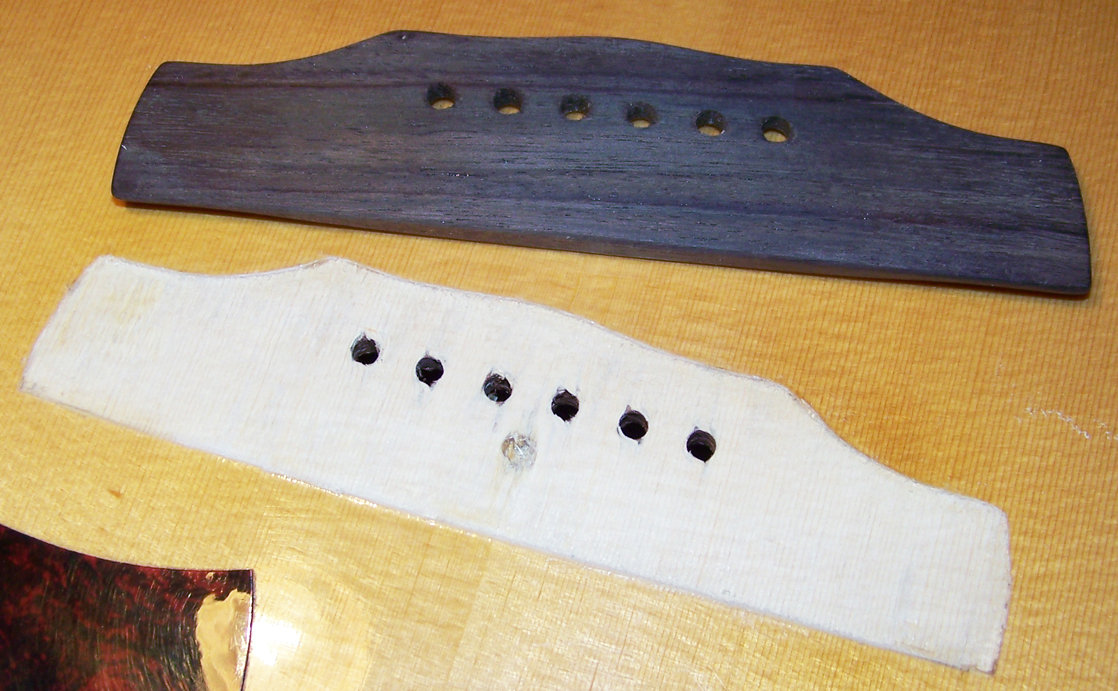

First I sanded down the edge of the bridge to remove the saw marks, and make it look as it should have in the first place, and flattened the bottom of it too, then I traced the bridge with pencil to the top, cut out the lacquer to fit and maximize the gluing surface, and sanded it down smooth, like so.

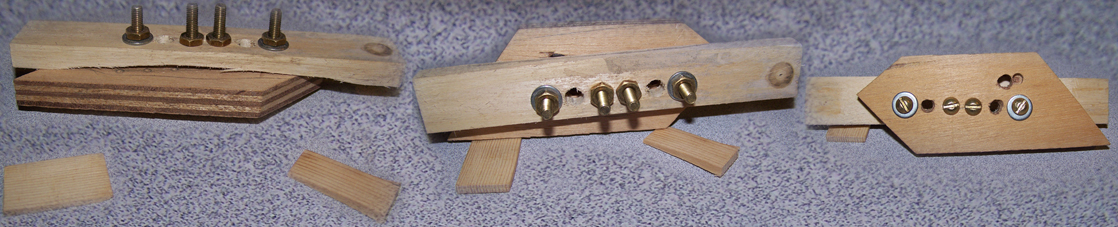

In order to glue the bridge back on, I made a jig to fit the top of the bridge, and the bridge plate underneath the top. They do make special clamps for gluing on bridges, but whenever there are bridge pins, this method works better for a few good reasons. Here is the jig:

It uses two plastic bridge pins the glue will not stick to, to align it, and four screws to apply pressure where it counts the most, and a few shims to apply pressure to the ends of the bridge. Here is the sequence of it being attached:

Thanks to water based glue, cleaning up squeeze out is a cinch. In case you are wondering, it is water proof once cured, heat resistant and also much stronger than hide glue. It would take a gorilla with a crowbar to remove it, in which case the wood would break before the glue joint. And no, hide glue is not better because it can be repaired, since good glue eliminates the need for repairs altogether.

After the glue was cured I cleaned out the peg holes and filled the saddle slot with a piece of wood dowel to prevent the saddle from going out of alignment. The arch in the top was nearly completely gone, and although the action was much lower, there was room to lower it a bit more by shaving down the saddle, and also lowering the rather high string groves in the nut, and improving the overall intonation by doing so.

With a better than when new action, more accurate intonation, and proper string alignment, this instrument was ready to be enjoyed again, more so than ever. Here are a few more pictures with it strung up to pitch. The first one shows where I filled in the saddle slot, after I blacked out the piece of dowel with a sharpie. You can also see the small slot in the edge of the saddle, which I do to make removing it easy for working on, since it fits tightly as it should, and removing saddles with pliers is difficult without scratching them up.

Well there is an obvious manufacturing flaw where the fingerboard meets the rosette and sound hole.

I dig the red perloid tuning knobs.